Language: An Ancient Tree

"Which ones are right?" Donna asks me.

I glance over the slides on the computer screen.

"This one needs to change, and this one," I tell her. "Oh, and this one. I can't stand the ________ Hymnal."

"Don't they use the same hymns?"

"Well, they change them, to make them more understandable to a modern audience."

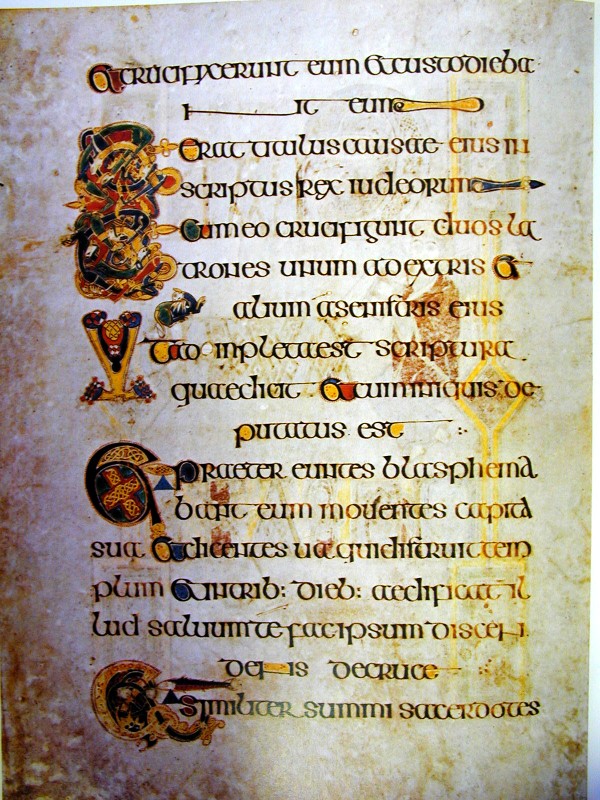

A familiar sight nowadays for those who read antiquated writing is the editorial process, eradicating commas and superfluous dashes like the little man behind the curtain. Pay no attention to him. I am the Great Oz. Yet, if we are not careful, we will be lulled into the loss of a language that is our heritage and runs in our blood. This is not, of course, popular. Modern folks don't like to admit that there are any strings attached to them, old, new, or yet to come. We like our so-called individuality, erroneous though it may be. "It takes a village to raise a child," goes the saying, but adults are not done being raised. We have an attachment to others, past and present, and we need it.

The reason editors, especially of hymnals and prayer books, do their well-meaning level best to disrupt this, is to provide us with sacred and venerated literature that is easy to understand. That's certainly helpful to those of us who are not scholars of Greek, Hebrew, Latin, Old High German, Middle English, Elizabethan English, Victorian syntax, and a host of other near-impregnable tongues and dialects that give shape to our history. Recently, I read my way through a theological work by George MacDonald (1824-1905), excellently edited by Michael Phillips. Syntactically, it was thick enough to read as it stood. I cannot imagine the difficulty without Phillips' help, though he gives some examples for reference.

However, with documents for corporate worship, and, I might summon the gumption to imagine, with the Scriptures (though that is certainly far above my head), the 'dumbing-down' of the language, by degrees and over time, dumbs down the congregation. Consider a quote by Madeleine L'Engle:

When I asked why, in the Prayer Book General Thanksgiving, God's inestimable love had been changed to immeasurable love, I was told that the laity found inestimable difficult. That's pretty condescending, in the nastiest sense of the word. Immeasurable is not simpler than inestimable, and in the context of that glorious prayer of Thanksgiving it is a weaker word. When I asked a multi-PhD-ed clergyman why the quick and the dead had been changed to the living and the dead, I was told that young people did not know the word, quick. I asked, "How are they going to know if you take it away from them?"

-Penguins and Golden Calves: Icons and Idols

What a great question. How will we ever learn the formal weight of "Thee" and "Thou" if they are replaced by "You" and "You," which not only use the same over-saturated word to express different parts of speech, but a word that we use to refer to ourselves in the informal? The differences are subtle, but over time they regraft our thinking like a grapevine to a trellis. No, L'Engle goes on to say, language should not be stunted. It is alive and should grow, but "the manipulation of language by the academic elite because they underestimate the ordinary, faithful churchgoer" is an objectionable thing. I would go on to say that a tree, growing larger in its bole year after year, does not leave the inner bark behind. Take a tree apart, and you will find that the inner bark had long ago become the scaffold by which the entire structure stood erect through gust and gale. So it is with language. To abandon the linguistic bastions of old, because some publisher thinks less of the intellect of the general public, is to speak a hollow tongue without meaning or poetry.

To recall the weight of He suffereth long over He is patient is to give credence to the truth that patience is a form of suffering, something that it makes us cringe to think. See the longing, however, of autistic kids' parents for a day without strife and stress, and see the longing of the children for a day of un-frustrated communication, and you will see that there is suffering in patience, and in love. This is only one of the ways that antiseptic language shift misdirects our thought, but the examples are manifold.

How amazing of children, though, to learn one word as quickly as another, even at a late age. Teach a teenager that "to know," in King James' parlance, means "to have sex with," and you have opened the door to a realm of understanding about intimate love that all the abstinence curriculum in the world never could. Yet as adults, with our underestimation of children's ability to learn, we often assume that our ability is not even so fresh and ready as theirs, though it is both ready and armed with greater experience.

Let not ship of thy attention run afoul on the slothful rocks.

1 Comments:

Ha ha ha! So true.

Post a Comment

<< Home