Art and the Church

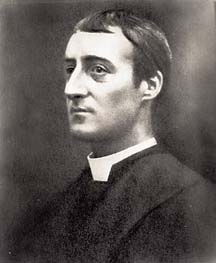

This is a letter I sent to a friend of mine after reading a letter by artist Makoto Fujimura. To be clear, my intent is not to whine or engender cynicism. As my wife consistently reminds me, we at Sinclair's Eve (our house) trust the Lord to provide. This still seems worth posting, if only as food for thought. The picture is of GM Hopkins.

In making music, writing books and poetry, in taking photographs, my ideas usually have to do with highlighting the beauty of this creation and the ways that it reflects on the Creator. In front of me at this moment is a photograph I took in Scotland, entitled "Sustenance." A board sits upon a restaurant table. Upon the board are a small glazed ceramic bowl of tomato bisque and a few crusts of homemade bread. The silver glint of a spoon twinkles out of the darkness beside the bowl, like a sword in a stone. I see the bread and hear the words, "Remember me." I can taste it just by seeing the photograph. I can hear the melodic tremor of Scottish voices around me in the cafe. I can feel the salt-sea chill sifting through the crossbeams of the ceiling, crying adventure down the street. The photograph is alive.

Yet, I walk past this and see six undeveloped rolls of film beside the front door, waiting like unopened gifts until the money appears. I've nearly forgotten all that is on them. I play shows with an album's worth of songs that have no home, wondering when the money will appear to fund the making of a record. It is a bitter thing to see building after antiseptically designed multi-million dollar building go up in the name of Jesus and wonder when I'll have to break down and flip burgers to feed my daughter. It is frustrating beyond description to see churches believe that they need projectors, sound systems, drum shields, mic stands, and computers upon computers just to be A church, and discover that none of it is offered in the support of my ministry (not to mention that none of it defines what the Church is). I say ministry - the work that I do, I do because I was made to do it. I am learning to come in to this idea. I can refuse, but not only would that be disobedient, it would destroy me as a person. I want to sing songs to you and tell you stories, that the God of Heaven might be magnified, that our consciences might be pricked. Not only that, I want to hear your responses. I don't want for many Good-Jobs and That-Was-Greats. I want to hear that the Holy Spirit brought Truth to bear in your life through what I did. Otherwise, my work feels worthless in the Kingdom. A great artist can effectively be rendered impotent by ceaseless praise, but can be en-Couraged and quickened by an account of how his art was a catalyst of holy change.

But how can I ask for money?

I, who have been given the task of seeing poverty and pain and bearing witness to the needs, cannot in good conscience speak of my own monetary need to the church. Children are sick and enslaved and hungry. I am disgusted at myself at times when I sit down with a plate of food in front of me. How can I ask for money? The welfare of people supersedes the development of film and an executive producer. Still though, at the end of the day, it would be good to have these things. I know that the war on poverty is endless, and I know that budget woes persist. But when the Church cannot answer difficult questions that the World (being the Devil's natural advocate) justifiably raises, I wonder why she, by the denial of her support, would silence the voices of those among her ranks who would ask the same questions in love.

As an addendum, let it be known that this is effectively the transcript of a personal inner argument for me. It is neither a manifesto or a doctrine. I do think the Church should support artists, and I believe Scripture supports this, but here again, if help is given because I or we complain, it might not be the help of a cheerful giver. I do not wish to deny the holy impulse people have to give unbidden.